Reiko Nireki’s Drawings and Objects

May Japan be defined by just one word? Hardly. But the simple word paper is able to evoke a number of classical Japanese characteristics. One thinks of its aesthetic quality and purity, of its transparency, lightness and adaptability. In its traditional making, paper is natural material based on fibre from trees and plants. It is one of the essential elements in the building of the traditional Japanese house, the gliding doors and windows (shoji) of which softly filter the light into the inner spaces – through paper. A structure made of wood, walls made of interwoven bamboo and covered with clay, the floor layed out with plant-made tatami, the roof formed by layers of straw or reed: the Japanese house is light and airy, fusing into nature being a part of it, and perfectly adapted to the humid climate and frequent earthquakes on the islands of Japan. However, in its purest form the Japanese home is a sophisticated piece of art, an aesthetic invention derived from nature of which it might borrow – in a refined way – by its positioning the sight of a wonderful tree or a mountain.

The artist Reiko Nireki returns to the principles of pre-modern Japan by using the same organic materials for her objects and drawings – japanese wa-shi paper as her essential element, earth, bamboo – and by letting abstract forms suggest rocks, mountains and trees. It is an intentional choice nourished by her love to nature and her critical approach to the contemporary world and its man-made disasters. Return to Nature is a romantic device regaining its value and a sense of urgency from the fact that in their striving for power, fast profit, cheap food and technical comfort our mass societies are capable and eventuall about to destroy the very basis of human existence on our planet. Is returning to an allegedly better past possible at all? Certainly not. But it is indeed our civil duty to denounce the odds, fatal mistakes and dead-ends of the industrial and technological heritage in favour of a safe future.

It is not the artist’s duty to provide whatever practical advice to this end, but – in a philosopher’s famous word – to remind us of ourselves. Reiko Nireki is well aware of the strange coexistence of pre-modern traditions and a super-modern surface of everyday life in her country, an ugly plastic world of business and efficiency, waste and scrap. Yet, within the structure of the village, which has survived Japanese modernization, the notion of the life-cycle, of the presence of our ancestors among the living is still alive. Thus, Nireki’s shadows have a real background. And they remind us western people that by unwisely exmitting our ancestors from our lives the natural cycle has been put out of balance.

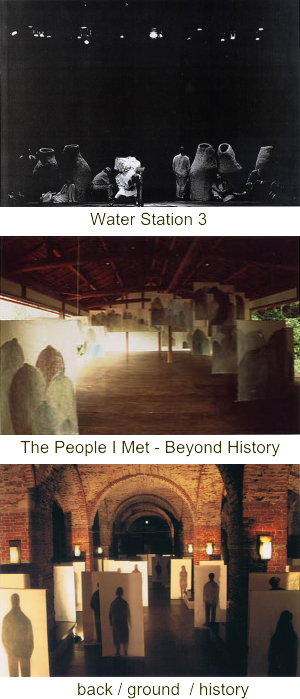

In the shape of Nireki’s huge anthropomorphic objects, made of a bamboo structure, paper-maché and clay, the ancestors have peopled the stage, in 1998, of Shogo Ohta’s play Water Station which has to do with the very question Nireki is asking – where do we come from, where are we going to, what is the meaning of life? Her objects may also be seen as cocoons able to generate life. In a show of the artist in Tokyo two years ago they saw themselves mirrored in a landscape of drawings hung from the ceiling (in the traditional way of the paper-scrolls), displaying massive black charcoal figures, army of shadows slowly passing away. Suggesting men and women with bent heads, or erect breasts, or huge upright rocks: they are a perfect image of Nireki’s interaction between human beings and nature. In her newest Helsinki project, exhibiting life-size drawings of people seen from behind, Reiko Nireki deals with the world of the living. These beings in different shades of darkness, turning away from us, seem indeed to be passing away as well. The artist, however, will let the shadows of the visitors interact with her backside people, thus creating a dialogue within our present world, with ourselves as mortal beings. Prerecorded voice letters are adding just another vital dimension to it.

made of a bamboo structure, paper-maché and clay, the ancestors have peopled the stage, in 1998, of Shogo Ohta’s play Water Station which has to do with the very question Nireki is asking – where do we come from, where are we going to, what is the meaning of life? Her objects may also be seen as cocoons able to generate life. In a show of the artist in Tokyo two years ago they saw themselves mirrored in a landscape of drawings hung from the ceiling (in the traditional way of the paper-scrolls), displaying massive black charcoal figures, army of shadows slowly passing away. Suggesting men and women with bent heads, or erect breasts, or huge upright rocks: they are a perfect image of Nireki’s interaction between human beings and nature. In her newest Helsinki project, exhibiting life-size drawings of people seen from behind, Reiko Nireki deals with the world of the living. These beings in different shades of darkness, turning away from us, seem indeed to be passing away as well. The artist, however, will let the shadows of the visitors interact with her backside people, thus creating a dialogue within our present world, with ourselves as mortal beings. Prerecorded voice letters are adding just another vital dimension to it.

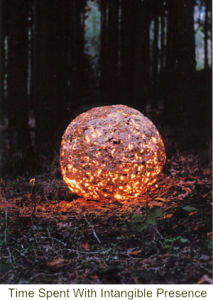

Reiko Nireki’s art questions the eternal secret of our existence.A big fireball glowing from inside whose surface seems to be cooling down – one of her recent objects – makes us think of our planet shortly after its creation, rotating deep down in time toward the moment of its being ready to give birth to life. Nireki’s messages are basic, devoid of technical or intellectual sophistication. Yet, the emotional and aesthetic impact of her art resides precisely in its straightforward simplicity.

Michael Haerdter

Art Critic

Former Director of Kunstler House Bethanien

Berlin / Germany / 2000